As Uganda continues to debate the legacy of President Yoweri Museveni, whose leadership has spanned nearly four decades, public opinion remains deeply divided. While critics point to concerns over democratic erosion and political repression, some Ugandans still credit Museveni with transforming a war-torn nation into a relatively stable economic and regional power.

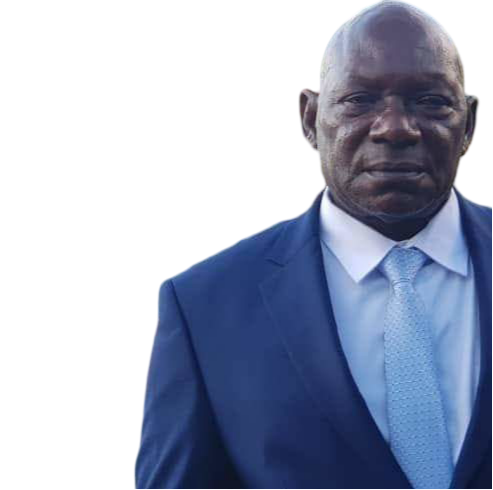

In a recent interview, Michael Waiswa Baluye, the Office of the National Chairman (ONC) coordinator for Buyende district and long-time supporter of the National Resistance Movement (NRM), shared his perspective on why he believes President Museveni’s long tenure has been beneficial for Uganda.

President Yoweri Kaguta Museveni has been in power since 1986. What do you see as his greatest achievement?

That’s easy – relative peace and stability. Before 1986, Uganda was a country ravaged by coups, dictatorships, and civil conflict. From Idi Amin to Milton Obote’s second regime, we saw endless cycles of bloodshed.

When President Museveni’s National Resistance Army (NRA) took power, they didn’t just win a war; they brought an ideology of disciplined governance. For nearly 40 years, we’ve not had a full-scale civil war. That’s a monumental shift, and it cannot be dismissed.

Critics argue that stability has come at the cost of democracy. How do you respond?

I understand the concern, especially among the youth. But let’s be honest, Uganda today is not perfect, but it is functional. President Museveni brought experience and continuity.

When you have a leader who has navigated the Cold War, regional conflicts, terrorism, and global economic crises, that institutional memory is invaluable. We don’t need abrupt changes that could destabilise the system. Leadership isn’t a popularity contest; it’s about who can steer the ship through storms.

How do experience and continuity factor into this support?

President Museveni’s long tenure is seen by us supporters as an advantage. We believe his experience enables him to manage regional security threats, diplomacy, and internal governance with fewer disruptions than a sudden leadership transition might cause.

Let’s talk about development. What has changed under President Museveni’s leadership?

Look at the roads. I remember travelling across the country in the 1980s and 1990s; it took days and weeks on terrible roads. Today? It’s under hours on paved highways. The same goes for electricity; access has more than tripled in the last two decades. Urban centres like Jinja, Gulu, and Arua are growing fast.

We now have industrial parks, new schools, and better hospitals. This didn’t happen by accident. It happened because of long-term planning. You can’t implement infrastructure projects over five-year election cycles and expect results. President Museveni’s longevity enabled consistency.

Some people say Uganda’s influence in the region has grown. Do you agree?

Absolutely. President Museveni is respected across Africa, not just as a leader, but as a strategic thinker. Uganda has contributed troops to AMISOM in Somalia, played a key role in mediating conflicts in South Sudan and the DRC, and remains a cornerstone of East African regional security.

That gives Uganda a voice on the global stage. We’re no longer seen as a backwater state; we’re a country that matters. And much of that diplomatic capital comes from President Museveni’s personal involvement and experience.

What about internal security? The LRA insurgency, for example, caused immense suffering.

President Museveni’s government is credited by us supporters for defeating or weakening insurgent groups such as the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) and for participating in regional and international efforts against extremist groups, which we say has improved national and regional security.

True—the LRA was a nightmare, especially in the North. But under President Museveni’s direction, the UPDF eventually degraded Joseph Kony’s forces to the point where they’re no longer a national threat. We also see Uganda playing active roles in countering Al-Shabaab and other extremist groups.

The security apparatus isn’t perfect, but it’s far more capable than it was in the 1980s. Ugandans today can travel, do business, and live without fear of rebel invasions or coups. That peace is priceless.

President Museveni is often seen as a Pan-Africanist. How important is that for a modern Uganda?

Very important. President Yoweri Museveni is often praised for advocating Pan-Africanism, African self-determination, and regional integration. We see him as a leader who resists excessive foreign political pressure and promotes African-led solutions.

He’s one of the few African leaders who consistently speaks out against foreign interference. Whether it’s rejecting conditional aid or advocating for regional integration through the African Continental Free Trade Area, he pushes for African self-determination.

He stood with Mandela, supported liberation movements, and still believes that Africa must solve its problems without Western imposition. That message resonates with many of us who want dignity and sovereignty.

How do supporters assess social and economic reforms under his leadership?

We point to gradual reforms in education, health, and the economy. Programmes such as Universal Primary Education (UPE), expansion of health services, and economic liberalisation are cited as milestones achieved during his presidency.

Universal primary education was revolutionary. Millions of children who would have never seen a classroom are now literate. We’ve expanded healthcare access, fought HIV/AIDS aggressively, and made strides in maternal health.

Economic liberalisation opened doors for private sector growth. Yes, youth unemployment remains a problem, and corruption is a challenge—but progress has been made. You can’t reform a broken system overnight.

Some fear that after President Museveni, Uganda might descend into chaos. Is that a legitimate concern?

A key concern among President Yoweri Museveni’s supporters is the fear that abrupt political change could trigger instability, unrest, or economic uncertainty. For us, continuity is seen as less risky than an untested transition.

We’ve had one dominant political figure for nearly four decades. A sudden vacuum could trigger power struggles. I’m not saying President Yoweri Museveni should rule forever, but a managed, peaceful transition is essential. The alternative? We risk repeating the chaos of the 1970s. Stability must come first, even as we push for reform.

What is the broader lesson for citizens, especially young people?

In a democracy, it is healthy for citizens to listen to multiple perspectives, critically examine evidence, and form independent opinions. Understanding why we support President Museveni does not require agreement—but it helps enrich national dialogue.