By Oweyegha-Afunaduula

From Disciplinary Silos to Holistic Solutions for the 21st Century

For generations, Uganda’s education system has been structured around rigid disciplinary lines—a model inherited from colonial pedagogy and later adapted for political compliance. This system produces graduates who are highly specialized in narrow fields but are often alienated from their communities and unprepared to tackle the interconnected, “wicked” problems of the modern world, such as climate change, food security, and ethical technological integration.

The digital age, dominated by the internet, social media, and artificial intelligence, demands a different kind of thinker. It requires minds that can integrate, innovate, and operate beyond traditional boundaries. The path forward lies in institutionalizing what we term the Sciences of Interconnectedness: a deliberate progression from interdisciplinary to crossdisciplinary, transdisciplinary, and ultimately, extradisciplinary learning.

The Framework of Interconnectedness: A Progression of Thought

To move forward, we must understand the distinct yet connected sciences that break down academic silos:

· Interdisciplinarity represents the first, crucial step beyond a single discipline. It involves integrating methods and insights from two or more disciplines to solve problems that one field cannot address alone. For example, developing a public health policy requires integrating medicine, statistics, economics, and sociology.

· Crossdisciplinarity involves viewing one subject through the lens of a completely different discipline. It’s the act of applying the logic of computer science to analyze historical patterns or using artistic principles to improve engineering design. This approach “master[s] different ways of working across subjects”.

· Transdisciplinarity transcends and unites academic disciplines to address complex real-world challenges. It focuses on the problem itself, such as sustainable agriculture or urban planning, and involves co-creating knowledge with stakeholders outside academia—farmers, community leaders, policymakers, and industry. As one program describes, it aims to “create an environment for University Students… to meet with experts and non-experts”. A visual analogy is a baked cake: once mixed, the individual ingredients (disciplines) are indistinguishable, creating something entirely new and unified.

· Extradisciplinary thought is the frontier. It operates entirely “beyond the disciplines,” free from their restrictions. It draws upon and validates knowledge from outside the formal academic canon, such as indigenous wisdom, traditional ecological knowledge, and community-based innovation. This is where true, unrestricted innovation in fields like information technology often begins.

From Theory to Practice: Seeds of Change in Uganda and Beyond

This framework is not merely theoretical. Pioneering initiatives in East Africa demonstrate its practical application and transformative potential:

· Agroecology as a Transdisciplinary Model: The Transdisciplinary Learning Initiatives (TDLI) programme, coordinated by Biovision Africa Trust in partnership with Makerere University, is a prime example. Its international training course brings together students, researchers, farmers, and policymakers to co-create solutions for sustainable agri-food systems. Learning moves sequentially from online theory to field excursions, practical data collection, and finally, workshops with farmers and policymakers. This model dissolves the wall between the university and the world it should serve.

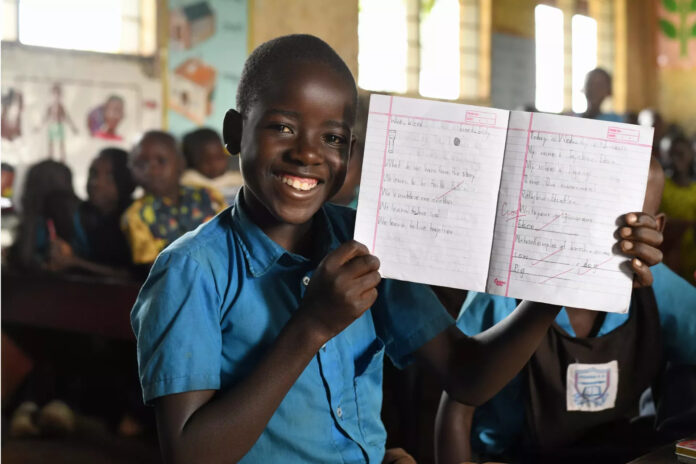

· The Power of University-Community Engagement: Research on Ugandan universities shows that community engagement programs create a vital feedback loop. Students and faculty gain real-world context and practical skills, while communities benefit from academic resources and collaborative problem-solving. This relationship is a practical engine for transdisciplinary and extradisciplinary learning, fostering “an improved understanding of community issues and the development of collective capacity”.

· A Foundational Mindset in Primary Education: Even at the primary level, institutions like the International School of Uganda are cultivating this integrative mindset through the International Baccalaureate’s Primary Years Programme. Learning is organized around broad, transdisciplinary themes like “How the world works” and “Sharing the planet,” uniting knowledge from language, mathematics, and science to build a holistic understanding from an early age.

A Blueprint for Action: Integrating Interconnectedness into Uganda’s System

For Uganda to harness these sciences, a multi-level strategy is required:

· For Policymakers & University Leadership: Mandate and fund the development of new, problem-centered degree programs and research institutes that are structured around themes (e.g., Water Security, Urban Futures) rather than departments. Revise promotion and tenure guidelines to reward collaborative, community-engaged research and teaching.

· For Educators & Curriculum Designers: Replace some traditional, single-subject courses with project-based modules. For instance, a module on “Lake Victoria’s Future” could integrate biology, economics, political science, and communication studies. Actively invite practitioners and community experts as guest lecturers and co-teachers.

· For Students & Scholars: Actively seek out courses and projects that challenge disciplinary boundaries. Develop the skill of “knowledge translation”—learning to communicate complex ideas across different fields and to the public. Embrace the identity of being a “team scientist”.

The resistance from entrenched disciplinary interests, which one source aptly characterizes as “slow professors,” is significant. Overcoming this requires courageous leadership and a societal recognition that the complexity of our era cannot be solved by the fragmented knowledge of the past.

Conclusion: Reconnecting Knowledge for a Sovereign Future

The call for the Sciences of Interconnectedness is more than an academic reform; it is a project of national reclamation and future-proofing. It seeks to heal the alienation between the educated elite and their communities, producing graduates who are not “Yes Sir” technicians but critical, innovative, and holistic problem-solvers.

By moving beyond the rigid disciplinarity of the 20th century, Uganda can educate citizens who are sovereign in thought, capable of ethical innovation, and equipped to navigate the uncertainties of the 21st century and beyond. The ingredients for this transformation—from transdisciplinary agricultural programs to community-engaged universities—already exist within our borders. What is needed now is the decisive will to mix them into a new, more nourishing future for Ugandan education.

For God and My Country.

Further Reading

Historical & Political Context of Uganda’s Education

· Reference: Kamya, B. (Date). Analysis of the Different Education Policy Reforms in Uganda, 1922-2000 [Working Paper].

· Why it fits: This academic analysis directly supports the article’s core critique. It argues that reforms from the colonial era through independence have failed to achieve quality and equity, leaving the system burdened by its past. This source is excellent for grounding your historical argument.

· Where to cite it: When discussing the colonial legacy and the failure of post-independence reforms to break from the rigid disciplinary model.

Foundational Frameworks for the “Sciences of Interconnectedness”

· Reference: Claremont Graduate University (2021). Abilities, Domains, and the Transdisciplinary Mindset. See also: Resources – Transdisciplinary Studies.

· Why it fits: These resources provide the authoritative, detailed definitions your article needs. They clearly differentiate interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary, and related concepts, and outline the specific abilities (e.g., integrative skills, effective collaboration) and competencies (e.g., systems thinking, design thinking) required.

· Where to cite it:

· In the section defining “Interdisciplinarity,””Transdisciplinarity,” etc.

· When describing the skills and mindset needed for future-ready graduates.

· Reference: Institute for the Future (2011). Future Work Skills 2020.

· Why it fits: This report forecasts that future work will require the ability to understand concepts across multiple disciplines. It provides external, global validation for the argument that integrative thinking is an economic and social imperative.

· Where to cite it: When making the case that the globalized world and future economy demand a shift away from siloed knowledge.

Practical Examples & Pathways for Uganda

· Reference: Laudato Youth Initiative (2025, September 22). Integrating Environmental Education into Uganda’s National Curricula: Unleashing Innovation for Agriculture, Biology, and Livelihoods.

· Why it fits: This is a powerful, timely Ugandan case study. It argues for a competence-based, holistic approach to environmental education that integrates science, indigenous knowledge, and ethics—a perfect example of transdisciplinary learning in action. It also references Uganda’s Vision 2040 and competence-based curriculum.

· Where to cite it:

· As a concrete example of a transdisciplinary model within the Ugandan context.

· When discussing the integration of indigenous knowledge and community-based learning.

· Reference: Oweyegha-Afunaduula, F. C. (2024). Advancing Environmental Public Learning in Uganda.

· Why it fits: This article is essential. It directly calls for adopting the “learning sciences of interdisciplinarity, crossdisciplinarity, transdisciplinarity and extradisciplinarity” in Ugandan universities. It provides the philosophical grounding for the multidimensional approach the article champions.

· Where to cite it: To anchor the entire argument in my own established scholarship on this topic, particularly when introducing the “Sciences of Interconnectedness.”

Additional Supporting References

· For benefits of interdisciplinary learning: Interdisciplinary Studies: Preparing Students for a Complex World discusses how it enhances critical thinking and problem-solving. Interdisciplinary Learning: Building Future-Ready Thinkers argues it builds skills for an interconnected world and mentions changing workforce demands.

· For pedagogical strategies: Linking Interdisciplinary Units to Real-World Issues offers a practical, step-by-step guide for designing interdisciplinary curricula around global themes.

For God and My Country

Prof. Oweyegha-Afunaduula is a Conservation Biologist and member of Center for Critical Thinking and Alternative Analysis